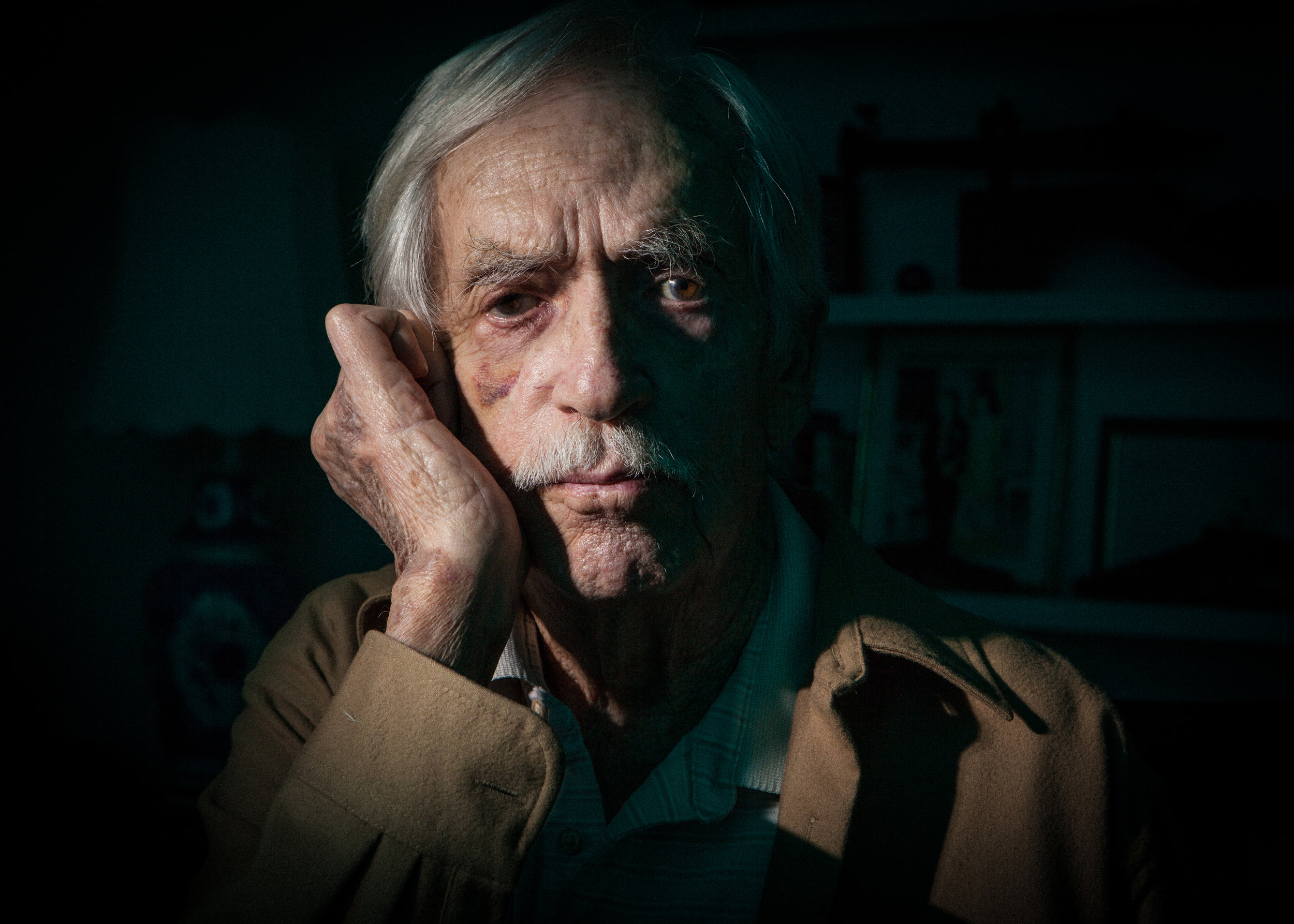

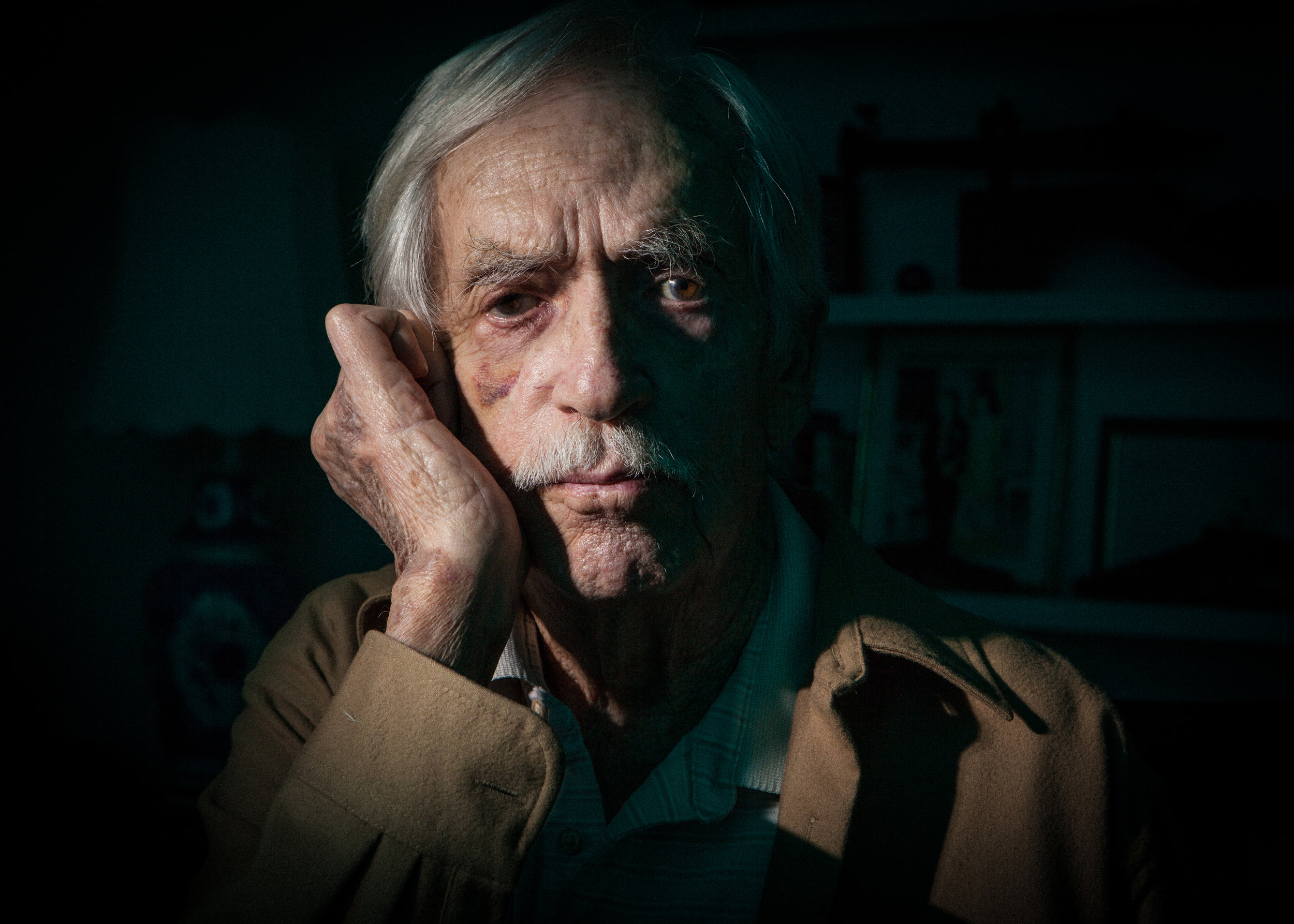

E.T. Roberts

12/23/1923

McAlester, OK

Army

Early morning on June 6, 1944, the hungry, sea-sick men of the 115th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, knew the “time had come.” Aboard their LCI and now making their way to Omaha Beach where they would become part of the second assault wave ashore in the D-Day invasion of Normandy. Unable to see over the landing ramp, the men knew they were approaching hell as both the sound of artillery fire and machine guns as well as the reek of gunpowder flooded the boat. PFC Earnest “E.T.” Roberts was stoically prepared to do the job that he knew had to be done. He was the lead man as the bow ramp came down.

Born on December 23, 1923, Earnest Thomas Roberts’s childhood was shielded from the harshest effects of the Great Depression because an oil boom had brought prosperity to McAlester, Oklahoma. The streets had even been paved with concrete and brick to replace the rutted dirt roads of his early childhood. As the son of a meat cutter with other family in the oil business, Earnest could devote his childhood to school, sports, like boxing and horses. The war that began in Europe was in the consciousness of most young men, and when the U.S. became involved, it was no surprise that E.T. was drafted at the age of 18.

Roberts did not travel far from home as his initial training took place at Camp Wolters, Texas, a bare 220 miles from where he grew up. While in training, he won the Camp Wolters Golden Gloves boxing championship and remained undefeated since soon after he shipped out to Fort Dix, New Jersey.

After arrival and further training, Roberts was scheduled leave to New York since the soldiers were on a schedule that depended on the troopships departing. The Queen Mary, however, arrived and was large enough to carry almost all the waiting troops. Just before departing on leave, Roberts was recalled to duty—and given the name of the AWOL soldier whose place he would be taking on the Queen Mary—as he was hustled aboard the ship to maximize troop capacity.

Once in England, training continued. Big training events involved landing on the English coast in small assault craft, moving inland several miles and digging into defensive positions, and conducting patrols and live ammunition firing for several days. In between these exercises, the men would march with full packs for 10-12 miles every day and practice digging constantly. After 17 months of training, Roberts felt he was an “Iron Man,” trained and ready for what lay ahead.

On June 4, 1944, the harbor was full. Before Roberts and the men loaded aboard their respective ships, he was able to watch as General Eisenhower spoke of their upcoming duty. With full packs, full loads of ammunition, and one field ration, they waited for their imminent movement to the beaches of France. That night as men ate their ration, the weather raged, and their small assault ships tossed about at anchor, but they did not depart. The following day, approval was given to initiate the assault with Roberts landing in the 2nd assault wave, scheduled to hit the beach at 0820 hours on June 6. After a long two days aboard the storm-tossed ship, the men hit the beach, sea-sick, tired, hungry, and as ready as their training and preparations could make them.

Roberts, the first man off the boat and into the frigid water which towered over him. His body went straight down with the weight of his pack, and everything he was carrying. His helmet caught the water and violently wrenched his neck causing him to drop his flamethrower and flounder through the water to the beach. As the sound deafened and the smoke choked, Roberts and his fellow soldiers crawled across the beach. E.T. crawled to one of the men who’d been shot and, E.T. having lost everything he was carrying, the young man told him to take his rifle. He’d been mortally wounded; his eyes turned blood red by the force of the shell blasts. Nonetheless, he urged Roberts to “shoot as many so-and-so’s as you can.” Roberts was eventually “gathered up by a sergeant” and moved inland to their first objective. By the end of the day, only he and seven others from his landing craft were still together. Replacements would start coming in a constant stream.

On July 5, 1944, as his unit approached Saint-Lo with artillery fire and flares lighting the way, they crossed an open field with only ¼ mile visibility. Suddenly, the enemy were among them. “I was slamming clips in from a bandolier. The M-1 was so hot I could hardly touch it.” One of his fellow soldiers hollered “Get him off my back!” Roberts turned and saw an enemy soldier clinging to his comrade. He shot the enemy off the man’s back. “When I turned back around, here come one right in my face just like that. I put the gun on him, pulled the trigger. He fired back; I saw nothing but flame.” E.T. describes when several rounds were fired by an enemy automatic weapon, one grazed his helmet, two penetrated his field jacket, and one hit his arm, passing through his bicep. Evacuated from the battlefield, he later returned and accompanied his unit fighting in the Netherlands and Belgium.

“You’re not trying to protect yourself; you’re trying to protect others. You’re trained as a group to take care of one another.” E.T. reflected on the actualities of combat compared to what is shown on TV or in the movies. “You’re carrying a 72-lb pack, wearing a 5-lb helmet, carrying a canteen and a heavy belt of ammo around you. You’re constantly having to lay down then get up, run, duck. And you do that until you get ‘er done.”

26 days after being shot at Saint-Lo, Roberts returned to duty. He recalled the intense pain of having his wound cleaned out and his admiration for the grit of a fellow patient, a lieutenant who had been shot 27 times, who had to have been in terrible pain but never complained. “He was one tough dude,” E.T. recalled, “I don’t know if he made it or not.”

During one combat operation, his lieutenant issued an order that Roberts knew would result in his men being killed. “He was a 90-day wonder; everything he knew was out of a book,” Roberts recalled. “I objected. I explained to him what I had to say about moving them up there. There was artillery fire being laid down right where he ordered me to move them.”

The lieutenant re-issued his order over ET’s objections. Roberts moved his men into position. When he was able to check on them, seven had been killed. One man, who Roberts had taken a liking to, had been gutted by mortar fire, his feet torn off, but still recognized E.T.

Roberts paused in tears from the memory. “I went back to the lieutenant and said, ‘You have three left. The rest of them are dead,” he remembered. The lieutenant took offense and sent Roberts to report to the lieutenant colonel. “I don’t want to listen to you,” he snapped.

The lieutenant colonel accused E.T. of being yellow-bellied. When Roberts explained that in his opinion soldiers had been unnecessarily slaughtered, the lieutenant colonel told him he would be court martialed. Ordered back to his lieutenant, Roberts recalled, “That was the last I ever heard of that.”

“I’m really lucky to be alive,” he continued. “What with the leadership we had at the last part of the war.”

For his service, Mr. Roberts was awarded a Purple Heart and five Bronze Stars. Returning to civilian life in Oklahoma, he didn’t find work that paid as much as he wanted so he headed to California after marrying his wife. They had two sons and were married for 66 years until his she passed away.

Mr. Roberts believed two years of compulsory military service would be beneficial for all young men. “It would bring out the goodness in them.” He observed that young men didn’t seem to want to work or provide for their families the way they used to. Military service he believed would help. “This is the type of stuff that needs to be cleaned up.”

Soloman Schwartz

09/15/1918

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Army Air Corps

Solomon Schwartz was twenty-three years old when he enlisted in the Army Air Corps. His unit was shipped to the Philippines that autumn, a place that forever changed him. Little did Solomon know that he was about to become a prisoner of war for forty-two months.

On December 8th, 1941, the Japanese began bombing the Philippine Islands. U.S. troops were ordered to leave the mainland for a place called Bataan, a little peninsula off the coast of the Philippines. Solomon’s unit helped set up a beach defense against the advancing Japanese army, but they were undersupplied and soon forced to concede. “Any American you talk to didn’t want to surrender.”

Solomon was among 60,000-80,000 American and Filipino soldiers who were rounded up by Japanese soldiers and forced to march over sixty miles in what became known as the infamous Bataan Death March. Solomon marched in the scorching sun without food or water. If a prisoner ran out of line to search for something to eat or was thrown food from Filipino civilians hiding in the jungle, they were killed. This pattern continued for days, countless men on the march were bayoneted or shot by the Japanese.

The only water available to drink along the march was contaminated by corpses. Solomon suffered from dysentery by the time he reached Camp O’Donnell, the prisoner of war camp. “I’m not sure how many days it took. It seemed like a lifetime to me.”

At Camp O’Donnell, the Americans and Filipino soldiers were separated into different areas. It was a decrepit old camp whose barracks were falling apart. There was not enough room for all the American prisoners, forcing two-thirds of them to sleep out in the open where it rained relentlessly. There were only two water fountains at the camp for thousands of prisoners. They had to stand in line for hours to get a canteen of water. The camp was so overrun by disease and filth that the Japanese never entered. Instead, they threw food over the fence. Solomon’s health quickly depleted from dysentery.

He wandered around the camp begging for food before collapsing into a slit trench. Two Marines helped pull Solomon out, bathed him, and scrounged food from other prisoners. Yet despite their efforts, his condition only grew worse. He was sent to a barracks for sick inmates, but everyone knew it was the place you went to die. Solomon couldn’t stand watching his comrades die next to him and mustered up enough strength to break out.

Solomon drifted in the camp, cold, naked, and covered in filth. He would crawl under the old barracks to keep out of the rain. He lived like this for four months when one day he found himself slumped on the ground from sickness. Two men were talking above him, one attempting to pick him up. “Let him lay there. He’s going to die,” the first man said. “No, we have orders to take him,” said the other.

They put Solomon on a truck and transferred him to Camp Cabanatuan, a prisoner of war camp where the death rate was sky high. Solomon beat the odds, and, within a few days, he began recuperating from his illness.

The Japanese army then began shipping prisoners to Japan for forced labor. When Solomon thought back to that treacherous journey, he recalled it being as bad, if not worse, than the Bataan Death March. They sailed on old freighters previously used for shipping horses. The two rooms on the ship held 1,000 prisoners and were so crowded that they were forced to sleep on top of each other. The horse manure and filth hadn’t been cleaned up.

Solomon had a canteen of water for the journey which was stolen one night. They weren’t given any water, forcing the prisoners to drink their own urine to stay alive. The trip took longer than they all expected as American dive bombers strafed the ships, not aware that thousands of Americans were aboard. Half of the ships bound for Japan sank on the way over.

When the freighters landed in Japan, the prisoners were loaded onto a train. “We were told if we opened up the windows and tried to escape the whole train would get killed.” They were taken to one of the worst prisoner of war camps in Japan—Fukuoka Camp #17. Solomon endured 12-15-hour days working in the coal mines while living off one handful of rice a day.

One winter night Solomon was spotted after curfew while attempting to bypass the guards. He was dragged into the guardhouse and ordered to take off his clothes. They dumped buckets of freezing water over his head, making him stand for two hours in the cold before locking him in a small wooden cage for a week.

When Solomon was released from the guardhouse, he went back to working long hours in the coal mines, walking two miles barefoot back and forth from the camp. “I didn’t have shoes on my feet for 3 1/2 years.”

On August 9, 1945 Solomon was working in the coal mines when the power suddenly went off. He climbed out of the dark mineshaft, discovering that the shaft had saved his life. He was only twenty miles away from Nagasaki where the atomic bomb had just been dropped.

By September, Solomon was a free man and managed to make the four-hundred-mile trek to an American air base. He had been a prisoner for forty-two months and weighed 81 pounds. Solomon was placed on a ship headed for the States, and, when it arrived, the crew was about to carry him to the dock on a stretcher. He refused. “I wouldn’t let them. I half crawled down.” He kneeled on American soil for the first time in over three years and kissed the ground.

After years of recovery, Solomon made his way back into civilian life. He married his wife, Betty, in 1947 and ran a jewelry shop in Beverly Hills for forty years, casting jewelry for celebrities such as Elvis Presley. When asked what kept him going during those horrific years as POW, Solomon said, “It’s just what you did. I was a prisoner and I didn’t want to die.”

Solomon frequently stated that “you have to live the best life you can.” For him, that meant forgiving the Japanese guards who beat him. Forgiveness gave Solomon freedom to live his best life.

George Hughes Jr.

06/22/1918

Loyalton, CA

Navy

Ensign George Hughes was performing calisthenics and simply “tossing telephone poles back and forth” with other trainees at Fort Pierce, Florida. At the end of the day, the exhausted trainees were told that “in the morning” they would do a little swim. At precisely, midnight instructors burst into the barracks rousting them from sleep. Loaded aboard a small boat, they were unceremoniously dumped into the ocean a mile from shore. Hughes was terrified of being in the ocean at night with only a compass and a watch. As he made his way to shore the words of his previous commanding officer rang through his head, “Your swimming is worth more than your engineering.”

Born on June 22, 1918 in Loyalton, California, George Hughes, Jr grew up in Oakland where both parents taught school. George grew up as an avid card player and competitive swimmer. Throughout his childhood and especially in high school, he practiced boxing, first under the tutelage of his father, a Golden Gloves champion, and later with his high school boxing team. The Great Depression had a tremendous impact, as often school teachers would not be paid, and, to help ends meet, George worked as a delivery boy for three different newspapers in Oakland. Graduating from high school in 1936, George attended Cal State University, playing water polo and completing a degree in mechanical engineering by 1940.

Industrial consortiums were working to expand industrial output, and George, an engineer for Consolidated Aircraft, was in the middle of planning the expansion of the B-24 fleet of aircraft. His goal was to increase production to 400 bombers per month. Because of his work, and the contacts he had working for military contracts, the attack at Pearl Harbor was not unexpected. The greatest difference for George pre- and post-Pearl Harbor was the fact that there was no longer enough time. His work became all-consuming as demands were ever increasing as wartime production ramped up.

George’s civilian employment came to a screeching halt when George and a few other engineers tried to change companies. Told directly by the Department of Labor that they were war essential workers and unable to quit, George and four others opted to enter direct military service.

Hughes attended his initial 90-day training in Tucson, Arizona, to be commissioned as a Construction Battalion officer for the U.S. Navy, where his commanding officer noted that he was a superb swimmer. Hughes received follow on training at the amphibious training center for Naval Construction Demolition Units established at Fort Pierce, Florida. A strict and rigorous initial training week weeded out the physically challenged members, and a one-mile surprise ocean swim removed others. Completing his training, he was sent to Waimanalo, Hawaii as the commander of a ten-man, clandestine operations team. Training in Hawaii was heavily geared towards the demolition of beach obstacles and testing new equipment. As a “frogman,” Hughes had definite combat roles and missions, but, as he stated, “we were doing experimental stuff … engineering essentially.” Experimentation and engineering brought no relief from the arduous physical training required in their primary role. Training included weekly 17-mile swims and practice “invasions” of Oahu.

George conducted 6 wartime missions. His first mission was also the most horrendous, resulting in the deaths of two men under his command. Flown by Navy Air to the island of Saipan, the naval commandoes lived a nocturnal life. Already secured by the Marine Corps, Saipan served as a bustling military communications and logistics center. However, Japanese holdouts in the jungle conducted nightly raids, killing, stealing, and damaging businesses and military property. The demolition teams had received jungle training in Florida and were pressed into service to interdict these holdout Japanese raiders. Armed only with battle knives, the Navy men began a nightly routine of observing jungle trails and ambushing Japanese as they sallied forth. Hughes characterized this mission as “killing men at night with knives,” crediting the speed and agility developed boxing as key to his survival. The mission ended when a sword wielding Japanese officer killed two of the naval commandoes. These men were of much more value performing their primary mission of demolition and were withdrawn.

A typical stealth mission involved meeting at the CINC-PAC Headquarters in Hawaii. Team leaders often received intelligence reports directly from Captain Ellis Zacharias, the leading signals intelligence officer and Japanese linguist. After additional mission specific training, the men would board PBY Catalina flying boats and rendezvous with submarine tenders at sea. Transferred to submarines, they would be transported and inserted near their objective areas. Armed only with battle knives, these men would swim ashore and conduct their missions, return to their submarine and depart.

One such mission had Hughes lead his men in the destruction of a radio station on the island of Formosa (modern-day Taiwan) where “Tokyo Rose” allegedly made transmissions at the time. Luckily, they were not detected and did not see Japanese soldiers on this mission. Hughes was unwilling to discuss other formerly classified missions but did play a role in recovering some of the Doolittle Raiders along the Chinese coast after their historic mission. As the war ended, he and his team were training for the invasion of the Japanese island of Hokkaido.

The end of the war saw the dissolution of the underwater demolition teams, and Hughes completed his Naval service assigned to the Engineering Department of the escort carrier USS Munda. Hughes returned to his career in aviation, serving as a project engineer for the AH-56 Cheyenne attack helicopter among other projects for Lockheed Corporation.

Refusing to characterize himself a hero he believes his service was a duty: “When your country’s in danger you are doing it.” Despite the horrors witnessed in combat, his only remark regarding his service is simple and fitting: “Just work. That’s all.”

A deeply religious man with strong opinions, Hughes nevertheless spoke precisely and technically as a lifelong engineer. Noting his own desire on returning from combat to go on a “one-way swim” into the ocean, Hughes was vehement in his criticism of the Veterans Administration for not doing more to assist the returning veterans of today and blamed government bureaucracy for denying these young veterans help. He was little surprised that the veteran suicide rate was so high. He was also quick to observe when asked directly for advice, “Work creates wealth; vacation uses wealth.”

Ernest Martinez

09/25/1921

Tularosa, NM

Army

PFC Ernest Martinez was born in the desert village of Tularosa in south central New Mexico in 1921, the first year the World Series was broadcast on the radio. His father had died before he was born, and his mother passed when he was 14, so he went to live with his grandmother. He and his five siblings grew up during the Great Depression in a world with no running water or refrigeration. He remembers growing up without shoes and that his childhood was miserable and hellish. He never got past the 3rd grade and finding a job during those trying times proved difficult. Ernest had heard about the December 7th Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor over the radio while hitchhiking home. After the broadcast he remembers thinking, “We are going to have to go to war.”

On January 6, 1943, he was inducted into the Army and shipped off to Camp Roberts, California, one of the largest military training facilities in the world at that time. His training continued in Alabama, which he recalls was “hotter than hell” with plenty of mosquitoes to keep a soldier company during the humid nights. He had heard that the Army needed paratroopers, who received 50 extra dollars a month for jump pay, so he volunteered and reported in to Fort Benning, Georgia, for jump school. Although he was not able to qualify as a paratrooper, he met all the requirements to become an infantry rifleman. He was transferred to Camp Myles Standish in Massachusetts, the departure area for more than a million Allied troops during the war. There he completed his final training and checked over his equipment including his M-1 service rifle. When it was his time to head overseas, he was sent to the port of Boston and boarded a ship destined for Liverpool, England.

Private Martinez, now a member of the 2nd Infantry Division, sailed to England in January 1944 to continue training for the massive invasion of the European mainland—Operation Overlord—codename for the Battle of Normandy. He landed at Omaha Beach in France on June 7, 1944, D-Day plus one. As the bullets whizzed by and the artillery exploded around him, he recalled telling his fellow GIs: “My ass belongs to the Germans, and my soul belongs to God.” His division was tasked with attacking across the Aure River, liberating Trevieres, on June 10th and proceeded to assault and secure Hill 192, a key enemy strongpoint on the road to St. Lo.

During the battle in an act of frustration, the young soldier mounted a bike and rode towards the German lines with his rifle slung over his shoulder. For no explainable reason, the German soldiers left their defensive positions, possibly dumbfounded by Ernest's brazen act, and the Americans were able to move forward. Once again Ernest was recognized for his bravery and was awarded the Silver Star.

In the Ardennes Forest, on October 18, 1944, Ernest was wounded in the leg and suffered a broken arm during a German artillery attack. He waited 20 minutes in a German pill box for the artillery to stop and the medics to arrive. He was whisked off to a hospital tent and then off to Paris for surgery. He received the Purple Heart for his injuries. He was transported back to England where they treated his wounds. At the time, he was worried that he may have to have his leg amputated, but the doctors were able to save his limb. He recovered in England for 6 months before being sent back to the States. He departed England in January 1945. As a parting gift from the war, he spent the whole trip back suffering from seasickness.

It felt good to be home after the war even though racial tensions were still a part of everyday life for Ernest. He recalls visiting El Paso, Texas, and reading a sign hung over the door of a local restaurant that warned potential customers, “We do not serve Blacks or Mexicans.” In the weeks, months, and years after returning from the war, he missed being with the whole gang that served so heroically overseas during World War II. After his discharge, he found re-integration with civilian life difficult as he had little education and few skills. He was able to live comfortably off the little money he had saved, supplemented by his benefits as a 100% disabled veteran. Martinez eventually settled in Los Angeles and worked repairing various machines used to make saddles. Throughout his life, he was haunted by the harrowing memories of the war and suffered from what is now known as PTSD. He recalls having to take pills to help sleep at night. He will not talk about the war unless somebody asks him. At night, he closes his eyes and pictures the hundreds of dead soldiers he saw on the battlefield.

For his heroic actions in Normandy, Northern France, and the Ardennes and for wounds he received in combat, PFC Ernest Martinez was awarded the Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, and the Combat Infantry Badge. He reminisced about the time he spent in a living hell in the fields and forests of war-torn Europe and stated simply, “I'm very proud I fought for this country.”

Lou Berger & Thomas Crosby

Thomas Crosby

09.29.1933

Mindanao, Philippines

Japanese POW

Louis Berger

05.29.1925

Philadelphia, PA

Army

Louis Berger grew up in Depression Era Philadelphia. Though times were taxing, his resilient Jewish family was not adversely impacted by the years of downturn. They had lived without luxuries before and were accustomed to a simple life. Growing up thin and small, Louis fondly remembers visiting the local drug store to buy an egg to put in his milkshake with the hopes of packing a little weight on his frame. He was 16 when he heard about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He remembers that the excitement all around him was spectacular. Though the country was not ready for war, America quickly mobilized, and many young American men began signing up for the service.

Across the Pacific, Thomas Crosby, born in the Philippines, resided south of Manila, in Pasay, with his mother, grandmother, aunt and little brother prior to the Japanese invasion. His mom had worked for the local chamber of commerce and grandma was a nurse at the Cavite Naval base. Thomas was eight when the Japanese struck the Philippines 10 hours after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. He remembers that during the invasion, he could see the Japanese planes dive bombing the capitol city of Manila. The invaders would quickly go on to destroy many American aircraft and march many allied soldiers to their deaths on their way from Bataan. Early in 1942, as things went from bad to worse in the Philippines, both General Douglas McArthur and the American Asiatic fleet withdrew to Australia and Java respectively.

Louis was drafted and shipped to Camp Haan, an Army anti-artillery base, in Riverside, California, for 7 months of training. Early in 1944, Louis remembers crossing under the Golden Gate Bridge, out of San Francisco Bay and across the Pacific, stopping briefly in Hawaii to re-stock. The young soldier was a member of the 385th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion, part of the 1st Cavalry Division. Along the way the ship picked up Navy Seabees and dropped them off in New Guinea, which the Japanese had invaded right after Pearl Harbor. The US had taken back the strategic island earlier in the war thus sparing Australia a certain invasion from the north. Louis spent several months in New Guinea before heading to conduct mop-up operations after the battle of Biak where 474 Americans lost their lives annihilating heavily entrenched Japanese soldiers.

In the Philippines, back in 1942, Thomas and his family were taken to Manila's Rizal stadium where they were separated from military personnel, put in trucks and then transported to the sprawling campus of the Catholic University of Santo Tomas. The university had been converted into a makeshift prisoner of war camp used to house civilians and US Army and Navy nurses. The Japanese made it clear that punishment for escape attempts would be severe. Early in the camp's history, three British civilians attempted to escape and were caught, beaten and then brought in front of the other prisoners where they were summarily judged then shot to death.

In October of 1944, Louis and his Army unit arrived in Leyte, then moved to Luzon, Jan. 9th. When General MacArthur heard the orders from Tokyo to eliminate all military and civilian POWs, he ordered rescue teams to advance and liberate prison camps in Manila. Louis was with the 1st Cavalry Division's "Flying Column" and the 44th Tank Battalion on February 3rd, when they began the rescue of the camp where Thomas had been held captive.

Thomas and his brother were in the Education Building, where they spent most of their nights, away from his mother, and the rest of his family. With the help of the Filipino Scouts, the Army subdued the Japanese guards, except for the commandant and 65 other guards, who moved Thomas, his brother, and 220 others up to the third floor, where a shoot-out and hostage siege began.

The captives were held hostage for 36 hours during tense negotiations. The end result was an exchange of civilian prisoners for the safe escort of the enemy, fully armed, who were marched a few blocks outside of camp and released to join the rest of the Japanese army.

A few days later, the Japanese counter attacked Santo Tomas, full of the rescued internees and the US Army. The enemy shelled them for four days resulting in many casualties, before elements of the 1st Cavalry and 37th Infantry Division could drive the enemy back. This was the beginning of the Battle of Manila. Manila was captured by the 1st Cavalry and the 37th Infantry Division on the 3rd of March 1945 and most of the Japanese resistance moved up to the hills above Manila. Louis and his unit were sent to help the 37th clear these hills. He heroically packed in and delivered shells to US mortarmen up the steep slopes. Louis recalls the bitter fight to take the memorial Rizal Stadium in what was called "Battle of the Ballpark." The Japanese, in their last stand against the liberators, fired their machine guns from the grandstands at the advancing American Infantrymen, who were seeking shelter behind tanks and doing their best to avoid land mines. Louis and his fellow GIs fought bravely and took the stadium, forcing the remaining Japanese to retreat and hide in boats down at the Pasig river. It took the Americans an additional two days to clear and secure the area. The battle for Manila had been a shot for shot, doorway to doorway, battle. The Japanese had been beaten into submission in the Battle for Manila and had lost thousands of soldiers to vicious urban combat where over 100,000 Filipino civilians were massacred by the Japanese as they were retreating.

When Thomas first met his emancipators, he had spent over three years in the Japanese POW camp. By then the camp had grown to over 4,400 internees, conditions were less than ideal. Thomas labored in the POW camp, pulling sanitation duty, picking weeds and carrying water. They slept on thin mats in a crowded room. He would use burnt wood chips to clean his teeth. They had very few belongings with them, as they were told to pack for three days when the Japanese first gathered them up, never imagining their captivity would last 37 months. Thomas and his family had lived off lugao which is watered down rice and the vegetables the prisoners had grown in their own gardens. The Japanese would rarely provide the internees with the Red Cross Packages that were intended for them; when they did receive the boxes, they were usually picked through first. Thomas recalls one Christmas where in his Red Cross box, there was a bar of Hershey’s chocolate. Very aware of the situation they were in, he and his brother would share the chocolate bar, by breaking it into pieces and taking only one lick per day to make it last as long as they could.

Food was scarce, and one day Thomas went picking through the garbage trying to scrounge whatever he could. He found some chicken bones that were picked clean but wanted to bring them to his grandmother hoping they could get the tiniest amount of desperately needed nutrition from the bones. He was caught by the guards and physically punished for doing so. Sometimes they boiled their own leather shoes to get any nutrition they could to survive, leaving Thomas barefoot for the rest of his imprisonment. Towards the end of his imprisonment he recalls that the Japanese Kempeitai ("Military Police Force") had taken over responsibility of guarding the camp. This unit was tougher on the prisoners due to their hard line counterinsurgency tactics.

Following the liberation, the Army assessed the health of the prisoners. Many of the adults had lost half their body weight due to beriberi. Now 11, Thomas weighed 48 pounds, his brother weighed even less.

Once the battle had ended and it was safe to leave the camp, Thomas and his family boarded the Liberty ship, S.S. Frank H. Evers and spent April sailing the South Pacific, stopping at various islands, picking up and dropping off supplies, USO performers and whatever else was needed, on their way to the mainland. They crossed the equator twice, before reaching San Francisco on May 8, 1945; V-E Day.

“It was the most memorable sight, sailing under the magnificent Golden Gate bridge on a beautiful clear day. I’ll never forget that day. It was my first day in America,” Thomas remembers.

When V-J Day, was declared, Thomas and his family were living in Vallejo, CA, where his mother found a job at the Mare Islands shipyard.

Louis returned home aboard the troop transport, USS Comet (APP-166). After arriving at port, the survivors were put aboard C-47 transport planes for the first leg of their journey home. After 18 hours in the air and aboard a train, Louis finally arrived in Harrisburg, PA for mustering out. He was discharged in four days and took a cab home, ending his experience in the Army. He went back to work for his family's food business. The US government provided returning GIs a 52/20 plan which guaranteed every service member $20 a week for 52 weeks. The returning heroes immediately began working to build up the American economy. GIs were provided low-interest, low down payment home loans and Louis was able to purchase a three-bedroom house for $11,000 with a $62 a month payment. Times were good again.

Later in life, Louis and his band were playing at a banquet in San Diego. He had found out that they were entertaining former POWs that had been interred in camps across the Philippines during WWII. That's where he met Tom. Though ‘breathing the same air’ during the war, the two brave men had never directly met; now doing the same decades later, this would be the start of a lasting friendship.

Sergeant Louis Berger offers the following advice to future generations: "Be very thankful that you live in the United States. Take care of your country, there is no better place to go from here."

Stanley Troutman

10/03/1917

South Pasadena, CA

War Correspondent

In 1937, twenty-year-old Stanley Troutman was employed at Acme News Agency where he mixed chemicals and performed mundane tasks. Six years later, he had risen in the ranks as a photographer and was given an opportunity that would change his life. It was 1943 when Stanley’s boss at Acme approached him about an opening for a war correspondent. “I really wasn’t that red hot about going because I had a wife and daughter. Well, my patriotism got the best of me and so I made the decision to go ahead.”

Stanley left his family and safe stateside job, voluntarily putting himself in harm’s way, with no military training and armed only with a 4x5 speed graphic camera. He was put on board the aircraft carrier Intrepid and shipped to the Pacific where he was to document the American fight against the Japanese Empire.

His first assignment was the invasion of Saipan. Dressed in Marine fatigues, sleeping in foxholes, and eating C-rations, Stanley endured the same hardships as most combat infantrymen would, with no gun to defend himself. The only thing Stanley was shooting was his camera. “If you were caught with a weapon, they could shoot you as a spy, but as a correspondent without a weapon you would be treated as a war prisoner.”

Stanley found himself in the middle of the action on a hill in Saipan. He threw himself flat on the ground as Japanese machine gun fire suddenly whizzed through the air. Stanley tried to shield himself from the bullets behind his speed graphic camera. “All I can remember is seeing a bullet hit the soldier to my right.”

Stanley stayed on Saipan for nearly a month before being sent to other Pacific islands, including Tinian, Guam, Peleliu, Leyte, Borneo, Manila, and Corregidor. When American troops invaded Corregidor, he made the mistake of going in too early.

“I was with the ninth wave going in. I thought everything seemed pretty secure.” A Japanese sniper aimed at Stanley’s landing craft on which eighteen men were aboard. Bullets flew around them, taking the lives of three men and wounding others.

Once on Corregidor, Stanley took photographs of General MacArthur who wanted to inspect the Malinta Tunnel which served as a bomb-proof storage and personnel bunker before becoming a hospital for wounded troops later on.

“He started down into the Malinta Tunnel by himself. I was the only photographer, questioning myself, do I go in or let him go?” Stanley was hesitant, wondering if Japanese snipers would start shooting at any moment, but he went in anyway. Thankfully, they emerged safely, and Stanley got his photographs.

Stanley sent his photographs to the War Picture Pool in Pearl Harbor where they were processed, proofed, and then sent to Acme. Acme sent copies of everything he took to the Associated Press, Life Magazine, and the International News Service.

In 1945, Stanley became a correspondent for the Air Force, giving them publicity as they began to separate themselves from the Army Air Corps. The Air Force gave the correspondents a literal trip around the world in an effort to show what the Air Force had done to help win the war.

Stanley was one of the first American journalists to document the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the atomic bombs had been dropped. Along with one other photographer and ten correspondents, they landed in Hiroshima a month to the day after the explosion. From the airplane as they prepared to land Stanley could see the amount of damage, describing the effects of the bomb as “a pebble dropping into a lake.”

The waves of the bomb spread far and wide, wiping out some areas while jumping over others. “It was hard for me to realize one bomb could do so much damage.” Stanley photographed Japanese civilians with burns on their bodies along with rubble and desolation the bomb left in its wake.

When Stanley returned home, he became a bureau manager for Acme in Los Angeles before working forty-two years at UCLA in cinematography. In 1956, he was given the opportunity to help film the Olympics in Australia. Stanley looks back on his full life with thankfulness. “I’ve had a fabulous life.”

Hershel Williams

10/02/1923

Quiet Dell, West Virginia

Marines

Marines were bored and anxious, as they sat offshore in their amphibious shipping. Corporal Williams was not even sure he would land. Unable to see the island, the Marines could hear an occasional explosion and see aircraft fly overhead, but Williams thought this would be a rerun of Saipan when his unit was not needed and remained aboard ship. At midnight the word was passed for “chow at 0300,” Williams and his fellow Marines knew they would eat the traditional steak and egg breakfast prior making an amphibious landing. The next morning, the Marines climbed down cargo nets into Higgins Boats amidst 10- to 12-foot waves and circled aimlessly for hours before returning to the ship. That evening they again prepared for a landing. On February 21, 1945 they ate a second breakfast of steak and eggs, but this time the beachhead was large enough that they could land on the paltry 2 ½ by 5-mile island of Iwo Jima.

Hershel Woodrow Williams grew up in the rural community of Quiet Dell, West Virginia, the youngest son of a dairy farmer. His early life of rising early to work and going to bed early was broken only by a few pleasures. The few free moments he had were spent playing games with his brothers, walking to and from school with his neighbors and occasionally going to town to watch a movie or to an uncle’s home to listen to the radio. High school proved to be challenging not because of academics, but because of his work load and lack of transportation.

Williams followed an older brother into the Civilian Conservation Corps and was sent to White Hall, Montana where he worked timber for the U.S. Government. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Williams was offered direct entry into the U.S. Army. Unwilling to join the Army, he set his eyes on the Marines and was sent home for enlistment under his own terms. Unable to enlist immediately at 17, Williams worked on the farm until his 18th birthday when he went to the Marine recruiter. Heartbroken, Williams was unable to join the Marines because at 5’6” he was too short. He returned home to work until he was permitted to enlist.

Regulations for the Marines changed, and the recruiter tracked Williams down offering him the opportunity to enlist. Hershel entered the Marine Corps but did not report until May when he was shipped to the Recruit Depot at San Diego, California. Recruit and infantry training were uneventful, as Williams had learned from his father not to question orders and do all tasks to the best of his ability.

Shipping overseas initially to New Caledonia and from there to his wartime unit—1st Battalion, 21st Marines, 3rd Division—at Guadalcanal. On Guadalcanal, he trained for combat duty as a demolition and flamethrower operator. Provided with disassembled flamethrowers and an instruction manual on the assemble and loading, it was up to his section to figure out how to employ the weapons! After trial and error, it was discovered that the best flame mixture was aviation gasoline and diesel fuel, and the ideal technique was to fire a line of flame at the base of the intended target and “roll” the flame into the target at ground level.

Loading aboard amphibious shipping in June 1944, Williams faced his first combat in the Mariana Islands. The landing at Saipan proved to be quickly accomplished and his 3rd Marine Division remained in reserve off shore during both the Saipan and Tinian landings. However, Williams did not have long to wait, and in July 1944 went ashore on the island of Guam. The conditions and terrain on Guam saw Williams fighting with a rifle instead of his flamethrower. Surviving two Japanese Banzai attacks, Williams concluded that “for them to die in war was honor, but we [Americans] will do everything to survive and help our fellows.” Despite the anxiety of fighting in the dense jungles, and the horrors of combat and mopping up operations, the island was secured in August.

Resting, refitting, and honing his skills, Williams remained until February 1945 when he loaded aboard shipping for an unknown operation. He soon learned it was Iwo Jima. After the first aborted attempt to land, he came ashore on the 3rd day of the battle. Corporal Williams was horrified at the chaos and carnage but continued doing his job to the best of his ability. Pushing into assigned positions at the edge of an airfield, Williams observed the American flag on Mount Suribachi, and then plunged headlong with his fellow Marines across the wide-open spaces of the airfield.

After taking horrendous casualties in crossing the airfield, his unit incurred a line of reinforced concrete pillboxes blocking the path, and Williams’ commanding officer asked if he could destroy the pillboxes. Saying simply “I’ll try,” Williams picked four Marines to provide cover fire and maneuvered towards the pillboxes. Williams crawled from cover and moved towards the first pill box, but his pole charge man, who was to hurl explosives into the pillboxes, was struck a glancing blow to the helmet by a bullet and went down. Williams continued the attack alone. Crawling into the crossfire of mutually supporting pill boxes, Williams methodically and relentlessly destroyed one position after another. Returning several times over the next four hours for more flamethrowers, Williams proved “instrumental in neutralizing one of the most fanatically defended strongpoints” of the campaign.

This was Williams’ last battle of the war and he returned home for discharge in November 1945. His last duty was to report to the White House where President Truman awarded him the Medal of Honor for his actions on February 23, 1945.

Williams remained in the Marine Corps Reserve retiring as a Chief Warrant Officer Four and later had a career in the Veterans Administration. Williams’s most satisfying and fulfilling experience has been working for the families of deceased military members. Working tirelessly, Williams assisted in the erection of the first Gold Star Families Memorial in a cemetery of Williams’s home state of West Virginia on October 2, 2013, which has been followed by more in almost every state and dozens of communities. As of this writing, 47 Gold Star Families Memorial Monuments are complete and 53 are in process in 41 states.

Allen Wallace

08/04/1925

Springfield, OH

Navy

Peering through the 3” gap between the protective plating of his 20mm Anti-Aircraft Gun, Steward 2nd Class Allen Wallace looked through the sights as he swiveled the gun. When “battle stations” were called, there were no extra personnel on a navy ship, and the USS Selfridge was no exception. Maybe tomorrow Wallace would return to the wardroom and once again set out the dinner service for the officers, but today he was a fighting sailor in the United States Navy. The first of three Japanese aircraft flew within range, and Wallace began shooting. By the end of the day, he and his shipmates would shoot down three Japanese attackers, but this was not Wallace’s first battle, nor would it be his last.

Born on August 4, 1925 in Springfield, Ohio, Allen Therell Wallace grew up on a small farm. One of eight children, Wallace and his siblings were tight nit and independent, rarely relying on others for anything that they could do for themselves. Necessity made their natural family bonds all the stronger. Allen was a member of the only African-American family in this corner of rural Ohio. Resistance to endemic racism began early for Allen with the mayor pressuring the school system to hold him back a year so the mayor’s son would not have to be in his class. Additionally, Allen was able to practice with the sports teams at his high school but unable to compete in the games and voted “least likely to succeed” by his student peers. Finally, an altercation with his high school principal and Allen’s refusal to apologize brought the end of his school days. Throughout his school years and into adulthood, Allen tolerated the subtle racist acts, but he never accepted that they were just. Following his father’s example, he never behaved as anything less than a man and while he hated racism, he did not hate people.

On December 7, 1941, Allen’s father came home from work and announced that “Hawaii is being bombed” to his sons working in the fields of the family farm. Having never been taught to fear another man, Allen reported for induction in 1943 and asked for service in the Army Air Corps, to which his processing clerk cheerfully called down the line “here comes another Sailor!” Unable to swim, young Wallace was denied training in the Constructions Battalions and instead was placed into the Cook and Steward Corps after his training at Bainbridge, MD.

Combat for Steward Wallace aboard the USS Selfridge involved escort and convoy duty in the Pacific until the Marianas Campaign where the Selfridge provided gunfire support to the invasions of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam and air picket patrols for the main fleet. Following this campaign, the Selfridge, deemed too old for continued service in the Pacific, was transferred to the Atlantic for service as a convoy escort. Wallace was unable to remain aboard ship after being hospitalized for kidney stones, and was instead transferred to the USS Beverly W. Reid, a destroyer escort that was soon tasked with duty as convoy flagship. Searching for German U-Boats and maneuvering to avoid torpedoes, Wallace completed his wartime naval service, obtaining the rank of Steward 2nd Class.

Throughout his naval service and afterwards, Wallace maintained his father’s belief that “if you are a man, be a man,” and conducted himself with dignity and pride earning the respect of the officers and men he served with, beginning with the white commanding officer of his recruit training company who in parting, shook his hand as he said “Good luck, Sailor.” Aboard ship he behaved appropriately for his rank and station, but would tolerate no racial slights, an attitude which the white officers and crew appreciated and defended. Following his discharge, he led an early protest in Ohio leading to the desegregation of local restaurants and refused to remain with employers that limited his advancement due to race or education.

Striking out for California, Wallace pursued a construction career, but after being denied jobs by the union, he ultimately started his own contracting business. Returning to Ohio so that his children could attend “country schools.” He watched as his children were able to compete in the sports of their choice where he had been denied the opportunity and excel both academically and athletically.

Wallace remains remarkably open and optimistic regarding race relations and extremely proud of his service during World War II. Having grown up with extreme racism and having aspects of racism manifest throughout his life, he maintains that his life has been a good one, and that improvements are occurring every day. Living his entire life refusing to be bitter but demanding “to be looked in the eye” like a man Wallace, embodies the fighting spirit of all Americans.

If pressed for advice, with the legacy of his fifty-four year “honeymoon marriage” he suggested you “keep your wife happy; you don’t have time for all the outside stuff.” Sagely, he added, “Talk and you can’t hear; listen and you’ll learn.”

Jack Gutman

12/19/1925

San Francisco, CA

Navy

Jack Gutman knew at an early age that he was a healer—not a fighter—as a medical corpsman treating the wounded during the Normandy invasion. He joined the Navy at 17 with his father’s permission and became a corpsman because he tested high on the aptitude tests. The sight of blood made him feel faint, and he thought he’d never make it through training. But he did, a course that had been compressed from 1 year to 6 months. “I got over my squeamishness about blood when they took us down to the morgue and showed us a dead body,” he said. Jack learned to catheterize, finish stitching surgery wounds: “All kinds of things you couldn’t do today as a medic.”

Growing up in a poor family, his mother made a lot of buckwheat kasha. They ate it sweetened and with vegetables. Meat was unheard of. One Christmas a wealthy woman showed up with a basket of food and presents, including a turkey with all the fixings. “It was like an angel had come,” Jack recalled. “The best Christmas I ever had.”

When he heard Pearl Harbor was attacked, Jack knew the U.S. would go to war. He followed the war’s course on the news while he waited to turn 17 and his dad would give him permission to enlist. Gutman chose the Navy because he wanted to have a nice bed to sleep in and clean sheets. On ship or on base, he always had a bed and 3 meals a day. “The poor Army guys and Marines hit the beach, always in the dirt. Little did I know what I was going to get into,” Jack said.

He shipped out to England on the RMS Aquitania, stacked into bunks along with thousands of other men. “You know you’re going to war. I was inhibited in a way and I felt insecure, but I had a good memory for jokes. I’d tell a joke to a couple of guys, they’d call more guys over. Next thing you know I’d be doing a show for 15 guys. It built my self-esteem and took my mind off of what was coming up.”

Gutman was assigned to a medical unit at a very large hospital. For five months, he and his workmates prepared it for something they could tell was going to be significant. “We were preparing for Normandy. We knew it was going to be something big but honest to God I had no idea it would be that devastating.”

While preparing the hospital they were “buzz bombed” by unmanned bombs. Under international rules, the hospital wasn’t supposed to be hit, but they were nervous because they knew unmanned bomb couldn’t tell they were an off-limits target. “Luckily, only one came close to us,” Jack recalled.

“I remember one time we were being bombed by regular German bombers. I think I was in the mess hall. I didn’t know God at the time. I was under a table and the bombs are dropping, everything was shaking. I remember a guy named Sully was on the floor and saying ‘God, if it’s my time to go, I’m ready’ and I thought ‘This guy’s insane’. But later I talked with him about his religion. He was a Catholic. He never asked me about my religion, but he gave me a Bible. I put it in the pocket of my shirt and figured it would stop a bullet. That was my mind at the time.”

While in England, he went on leave from time to time. “I met a very nice English girl and fell in love. I used to bring her family oranges and eggs. I would see her whenever we got leave. We would go to the pubs and drink warm beer! And fish and chips for 20 cents,” Jack smiled.

“We thought Normandy was going to be a cakewalk because we’d seen all the mortar fire, the bombardment of the coast before the invasion. Then I saw all the American bodies and thought ‘Why are all these men dying?’ Afterward I wanted to find out why they had died. 9,000 men died in Normandy, 14,000 in Okinawa,” he reflected, overcome with emotion at the memory.

“Later I read that we had 11,000 bombers that were supposed to render the bunkers along Utah and Normandy helpless. But what happened as they were coming over is there was cloud cover and they said ‘We cannot see the bunkers, so when you think you’re near the beach count 3 and drop the bombs.’

“Well, the bombs dropped a mile away from the bunkers, and the only thing that hit them was the shells from the ships. So, therefore, all these guys—our guys—caught it all, the waves of troops just caught hell. We had practiced that the boats took you right up to the beach, and you jumped out and ran up onto the sand. But what happened was there were these barriers, and the men had to jump out into the water and wade through up to their waist or neck. Some of them panicked and jumped over the side. With their heavy packs, the water was so deep, they went right down. If they couldn’t get the pack off, they drowned. So, a lot of guys died that way and when you see bodies floating around it’s just . . .” he paused. “And always remember I was just 18 years of age.”

“It was a lot. It was more than I anticipated. It was sheer hell. You always feel: did I do enough for them?” “A lot of guys you save, but then a lot of guys die,” he said, again overcome with emotion. “And you kinda wonder, did you do enough?” Gutman said as he wiped away tears. “That brought up post-traumatic stress and so forth.”

Gutman chose not to talk about his experiences for many years. He would walk away from a conversation among veterans rather than participate. “I remember taking care of a patient who’d been wounded. He’d lost spinal fluid. And when you lose spinal fluid, you die. I would change the bandage, and the fluid would just shoot up. I asked the doctor ‘How is he going to make it?’ The doctor said ‘He won’t make it, he’s going to die.’ The guy would talk to me. He would tell me about his wife and his kid,” Jack said. “He tells me all about it and says ‘I’m going to go home soon and see my family, won’t I, Doc?’ and I said, ‘Yeah.’ You hadda lie to him, give him hope.” He paused. “And you take it personal,” he said tearfully. “If he dies on your watch, whoever’s on duty has to pack every cavity in his body with cotton. I had to do this, between here and Okinawa, four times. And it takes a toll on you ‘cause you get to know the person. It becomes personal.”

“I think,” he paused and cleared his throat, “I think that’s what I went through a lot, figuring why did this man die and I lived . . . and then with the flashbacks and everything it was driving me crazy. My flashbacks—I keep seeing the invasion, and it’s amplified. The guy screaming ‘Mama! Mama!’ and all that. It gets really horrible. Some of those guys never got back to their mother. I don’t want people to forget those guys who died or were badly wounded because they thought it was the right thing to do.”

During the invasion, he recalled being shocked to look over and see someone dead, someone he’d been joking with a little while before. At times, to shield himself from being shot, he dragged a body over for cover. “It was survival,” he stated. “We didn’t find out until we were out—I think maybe on the 4th of June. The invasion was originally scheduled for June 5th, but the water was so rough it flipped tanks off the transports and they sank with their crew.

“Rommel thought because of the weather the invasion wouldn’t happen for several more weeks, so he went back to Germany for his wife’s birthday party,” Gutman recounted. “Rommel and Hitler were the only two with authority to move a Panzer unit, which the Germans desperately needed at Normandy, but because Rommel was away and Hitler was asleep and ‘not to be woken’ according to his aides, the unit wasn’t dispatched to Normandy. God must have been looking after us,” Gutman said, “Because otherwise we would have lost more men.”

As they approached the beach, some of the men were so seasick they were vomiting on each other and felt so miserable they didn’t care if they lived or died. Gutman remembers people yelling, “Keep your damn head down!” as their boat crept through the mist and rough water.

They passed ships that had been hit. Gutman heard men yelling for help, but his strict instructions were “You’re not a rescue ship. Go do your job.” He was torn up to leave them, but he carried on to shore. “Then you wonder,” he said, “Did they make it or what? A lot of them hit the mines and got blown up.”

There was no time to triage the wounded in the heat of battle. “You just moved from one guy to the other. Sometimes the guy who screams the loudest is the one you go to. You do what you can, move from one to the next, give a morphine shot, staunch the bleeding, tag ‘em. Then a stretcher bearer would take them. If you see a guy there’s no hope for him, you give him a shot, give him some care, and move on . . . and you wonder, did you make the right decision? You wonder if you’re responsible for someone dying. That stays with a young mind. Some of them wanted me to stay with them, but I had to tell them I had to move on and another corpsman would be along to help.”

“There was a lot of bodies. All I knew, I was hitting the beach. My job was to tend to the wounded, evacuate ‘em, and get off whenever they call you.”

“It was 6 or 7 hours of hell I was there,” he recalled, “until I was told to get back to the ship.” But even after leaving the beach, Jack helped out with surgeries and setting broken bones. Always he wondered, “Could I have done anything more?”

Jack was haunted by his memories. While on leave after Normandy, he began to have flashbacks, although he didn’t know what they were. “We didn’t know about post-traumatic stress. Back then it was called battle fatigue. And we figured we’d get over it. But I had to have 3 1/2 years of therapy to get over it,” he said.

“I did crazy things. I gave money away to people. I wound up broke, almost cost me my marriage. I was drinking heavy. I got to drinking so badly. I think my downfall was at Thanksgiving dinner with my family, playing with the kids, drinking. When they served dinner, my face fell into the plate. I passed out in front of my family,” he said. “It was so embarrassing when I found out later. They were going to have an intervention, and I would have been so angry.”

“The drinking was a gradual thing as the flashbacks happened. I kept drinking a little more over the years.” Through the help of his daughter, a therapist, he was able to get sober. “She’s been a great help to me.”

After the invasion, Jack figured he would be sent stateside for an assignment. Instead, after 30 days of leave, he was shipped to Okinawa after he trained with the Marines in California and was assigned to what was called the Beach Battalion.

His time in training turned out to be traumatic. Two men had dug their foxhole too close to the road. They were run over by a tank while they slept. Jack was sent over to the scene, and the carnage he saw tormented him for years.

When he found out he was going to be in the invasion of Okinawa, Jack felt discouraged. After the horrors of Normandy, he had badly wanted an assignment in the U.S. “But when we hit there, it wasn’t like Normandy. There was some firing and wounded, but there wasn’t much going on on the beach. Most of the fighting was inland.

“We took on a lot of wounded. I was up on deck, taking a break, smoking a cigarette, when all of a sudden, I heard the alarm go off for battle stations. The big gun near me went off—BOOM!—and my ears were ringing. I was running along the deck and looked up and there were swarms of Japanese planes overhead. I looked over to the battleship New Mexico, looked up and saw a plane so close I could see the pilot, with that stern expression Japanese pilots have. He veered off and crashed into the New Mexico. We found out later he killed 80 people and the captain. The explosion was horrendous. I saw that. I just froze there, thinking that I’d just seen that man alive, and he purposefully killed himself. At that time, it was unheard of. I thought, are these people crazy? Are they lunatics?”

Gutman was 18. He lost half the hearing in one ear from the blast of the big gun. He described his experiences in Okinawa as traumatic, but not as bad as Normandy. The wounded men and their cries wrenched his heart, but he knew he was there to heal and to help.

Shortly before his birthday, in December 1945, Jack was discharged and returned home for Christmas to surprise his family, who threw him a big party. It was the second-best Christmas he'd ever had after the one where the rich woman brought dinner and presents for his family when he was a kid.

“I often wondered: why did God save me and my buddies died? Then I look around at my children and all they’ve accomplished. I’m very proud of what they’ve done. God has a plan that’s just amazing.” Even during times of hardship, decades later, Mr. Gutman asked God for guidance. “Touch lives,” was the message he received. He dedicated his life to helping others.

“I talked to one young man who asked me if World War II was a big war. That’s why I speak at schools. I don’t want them to forget. As long as I’m going to be alive, I’m going to speak about them and honor their names,” Jack declared.

“I saw you at the beaches, I saw you cry and die, and some of you got well, which I’m grateful for. But I’m grateful that you fought for your country. I admire you, I will always praise you, and defend you. I love you with all my heart. To my dying day, I will always be fighting for you however many days and years God has for me. I thank you from the bottom of my heart.”

Adolfo Celaya

05/16/1927

Florence, AZ

Navy

Adolfo Celaya was sixteen years old when a Navy recruitment sign caught his eye at the local post office. “Join the Navy, See the World.” Like other sailors, he soon realized that he wouldn’t see the world in the way he imagined. The choppy sea and raging war were the only things on his Naval itinerary.

That year all that Adolfo wanted for his seventeenth birthday was for his father to sign his enlistment paper. “My dad didn't want to sign and so I asked if he would for my birthday, if he'd give me that present.” His father relented and Adolfo was inducted into the U.S. Navy in August 1944.

He took his basic training in San Diego where he went to fireman training school. He began to experience prejudice in the ranks for being Mexican-American. All throughout his time in the Navy he never fully escaped from discrimination. Adolfo and fellow Hispanic soldiers were given the lowest tasks.

“Any jobs that were not taken by a white person would be given down to anybody that had Hispanic blood. You couldn't do anything about it. If you tried, it got worse.”

Adolfo had never set foot on a ship until he was assigned to the USS Indianapolis. It was a foggy night when the 1200-man crew was taken to the ship off the coast of San Francisco. A cloud of darkness veiled the ship as they were led to their hammocks. It wasn’t until morning that Adolfo saw the ship for the first time.

“I got up, went outside, and looked at that thing. My God, I wanted to get the hell out of there right away. It was big.”

They set sail shortly after Christmas, heading to Pearl Harbor before continuing on to their first combat mission on the island of Iwo Jima. The USS Indianapolis was five miles out as they bombarded the island before U.S. Marines landed. Adolfo saw kamikaze planes burn up in flames and heard relentless explosions everywhere he turned.

“I remember saying ‘This isn't what I joined the Navy for! I joined the Navy to see the world, not to get shot at.’”

Adolfo watched as transports of Marines arrived on landing barges right beside his ship as they prepared to storm the island. He was eyewitness to an iconic moment in history—the first flag raising on Iwo Jima. A comrade pulled him over to watch the event unfold through his binoculars. At seventeen years old and already jaded by war, he threw the binoculars back at his crew mate. “Ah, big deal.”

After twenty-five days at Iwo Jima, the USS Indianapolis was sent to Okinawa where they assisted with beach defense. The USS Indianapolis is credited with shooting down six Japanese fighter planes. But things were about to take a turn for the worse. Adolfo was walking towards the front of the ship when he saw a kamikaze plane coming in at a fast pace. It dropped a bomb on the ship before crashing. The attack resulted in several American casualties.

The USS Indianapolis was sent back to California for repairs, they were chosen for a secret mission which Adolfo didn’t learn about until after the war. They were selected to transport the components of the Little Boy atomic bomb to the island of Tinian from which the B-29 Enola Gay would make its mission to Hiroshima. Adolfo saw boxes onboard that were guarded by Marines, but he could only guess their contents. “I joked it was whiskey for the general or something.”

The USS Indianapolis set a record speed as they made their way, unescorted, to Tinian where they delivered the mysterious boxes. After unloading their cargo, they made their way to Guam where they were ordered to rendezvous with other ships in the Leyte Gulf. Without submarine detection gear, they requested to be accompanied by a destroyer. Their request was denied, and they had to make the journey again, unescorted.

Disaster struck on July 30th, 1945. A Japanese submarine fired two torpedoes at the USS Indianapolis. Before the first torpedo struck, Adolfo was sleeping below deck when his crew chief told him to come upstairs on account of the unbearable heat that night. The top deck of the ship was crowded with sailors trying to sleep. Adolfo managed to find a little space in the middle and fell asleep with his blanket draped over him despite the heat. Having grown up always sleeping with a blanket because of pesky mosquitoes, the habit ended up saving his life.

When the first torpedo struck the front of the ship, fire from the explosion burst through the middle of the deck where Adolfo was sleeping. It completely disintegrated his blanket. He could only open his eyes to small slits as he tried to run from the fire. His eyebrows and eyelashes were gone, his hair singed. “If I hadn't had my blanket on, I would have been burned up.”

He couldn't see, could only hear the mayhem happening around him. He ran to the back of the ship, a fiery blur in his eyes as the second torpedo hit the ammunition dump. The explosion was deafening, and he felt the ship rock and begin to sink. Adolfo didn’t have his life jacket and was trying to go downstairs to retrieve it from his locker when a friend stopped him.

“Stay with me and you can stay afloat on my jacket,” his friend said.

His friend jumped off the side of the ship, about two stories high, while Adolfo followed next. Sailors were shouting in panic as the ship went down. Twelve minutes passed before it was swallowed by the sea. Adolfo hit something on his jump down and was sick with worry that he landed on his friend. He swam away from the ship as quickly as he could, managing to open his eyes just enough to catch the end of the ship go down into murky water. Twelve minutes prior he was sleeping comfortably. Now he was in the ocean and his ship was gone.

“I was scared as hell.”

It was pitch black. The moon came in and out of the clouds, giving light for short periods of time before masking the ocean in complete darkness. Adolfo was a good swimmer, but this was different from the canals of his childhood. “The ocean was a lot tougher than I was.” He managed to get ahold of the side of a life raft to stay afloat.

Time moved slowly during that first day in ocean. “I thought we'd be picked up within hours or within a day. I never thought we'd be there five days.” The bickering, fighting sailors began to agree on one thing—nobody knew they were stranded out at sea. “After the third day I started thinking the same as the other guys. I guess they’re not going to pick us up.”

The sun beat down on them in the day and the ocean was bitterly cold at night. Adolfo’s hope of rescue began to fade. There was nothing to drink and sleep was dangerous. While other sailors had friends to help them keep afloat while they slept, Adolfo was on his own. He tied his t-shirt around a rope on the raft, securing himself to the side and managed to catch small spurts of sleep.

Because Adolfo could easily swim around without the weight of a life jacket, he brought sailors to the edge of the raft who were drifting away from the group. By the second day, he was exhausted and couldn’t save the sailors anymore.

Some gave up and let themselves drift off. Sharks lurked under the water, and he heard the screams of sailors as they were attacked from beneath the surface. If the weather was clear, he could see the sharks stalking their prey along the surface. Thirsty sailors couldn’t stand it anymore and began drinking the salt water. They began hallucinating, and many were lost to the sea. Before Adolfo left for the war, his mother gave him a medal of Saint James that gave him the courage to keep going. For days he held on and tried to keep his crew chief alive.

“I think he kept drinking salt water. If I could have gotten him onto the raft, I could have kept him alive, but I asked the guys up on the raft and they pushed me under water.”

On the third night, Adolfo was sure he was hallucinating when he heard Spanish voices in the distance. The next morning, he swam around the large group of sailors and there was his friend whom he thought he had killed when he jumped from the ship. Adolfo was relieved to see him, but soon had to swim back to his crew chief to make sure he was all right. When he got back to the raft, Adolfo discovered that he wasn’t there anymore. His chief had untied himself and was waving goodbye as the waves took him away.

On the fourth day, they were discovered by American pilot Lieutenant Wilbur “Chuck” Gwinn. Somebody yelled that they saw a plane, and when it circled over their area and tipped its wings, Adolfo breathed with relief, knowing they had been discovered. “Everybody was in bad shape. I don't think many could go another few days.” Out of the 1200-man crew, only 317 survived.

Lieutenant Gwinn signaled an alert to the nearest American base on Peleliu. A seaplane rescued some of the survivors that day. Adolfo had to wait until the following day when he was saved by the crew of the USS Bassett. The USS Bassett took the survivors to a base hospital in Guam where Adolfo began to recover. After a month they were sent home to the states. On the journey home, Adolfo heard that the bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. At that time, he still had no idea that the USS Indianapolis transported the bomb components.

Another trial soon began for Adolfo on the trip home aboard an aircraft carrier. For three days in a row he was picked for work detail on the ship, the same old prejudice against him ever present. He was still recovering and told the Lieutenant that he thought it was time he picked somebody else from the crew. “We have another 300 survivors here that could probably do a little bit.”

He was sentenced to two days of solitary confinement with only bread and water to eat and drink, for insubordination. When the ship reached San Diego, he spent another five days in confinement locked inside a small cubby hole just a month and half after being rescued from the ocean. He was then taken to Long Beach Naval hospital and was discharged from the Navy. “When I was discharged, they gave me fifty percent disability and told me I could not join the Navy again. I said, ‘Why that's a blessing!’”

Upon returning home Adolfo, at age eighteen, suffered from what we now know as post-traumatic stress. He stills suffers from nightmares from those long days lost at sea. It took nearly thirty years before Adolfo could share his story. Once he started, it was a healing process for him. “I'm just glad I'm alive. I'm glad I'm here.” Adolfo’s hope is that young Americans will learn and care about the history of WWII and have respect for those young, tough boys who won the war.

Muriel Engelman

01/12/1921

Meriden, CT

Army

Muriel always wanted to be a nurse. After graduating from high school, she applied for nurse’s training in Cambridge, Massachusetts. While in her second year of training, Pearl Harbor was bombed and war was declared the next day. Muriel and her classmates knew that nurses would be needed and upon graduation a year later, Muriel enlisted in the Army.

She was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corps in April 1943, and her first post was at Fort Adams, Newport, Rhode Island where she cared for everyday illnesses and accident cases. As the war in Europe heated up, Muriel requested overseas duty and was soon sent to Fort Devens, Massachusetts to join up with the 16th General Hospital. For six months, the nurses trained for with fifteen-mile hikes, daily calisthenics, classes in communicable diseases, learning how to descend a swaying rope ladder under full backpack, and going through the Infiltration Course on hands and knees under live ammunition.

Finally, the last week in December 1943, they boarded ship for Liverpool, England. Because their hospital was not yet ready for operation, the hospital personnel remained on detached service with the nearby 304th General Hospital. Many of the staff were there as patients because they had developed the “English Hack,” a body wracking cough from the cold, damp winter weather. As the weeks passed, time was spent setting up the 16th General Hospital in preparation for the coming invasion of France, date unknown at this point.

On June 6, 1944, D-Day arrived, when the Americans crossed the English Channel and invaded the German held Normandy coastline. About 6 weeks later the 16th General Hospital debarked at Utah Beach in a trip that should have taken 3-4 hours to make the twenty-one-mile crossing but took three nights and almost four days because the Channel was still littered with the debris of fallen planes and half-sunken ships from D-Day. Complete blackout conditions had to be maintained at all times as German planes were still flying overhead, and even a lighted cigarette could prove disastrous for the Allies.

The hospital unit camped out in a Normandy cow pasture for the next seven weeks waiting for the Germans to be cleared out of Liège, Belgium so that the hospital could move up to Belgium and establish their tent hospital in an apple orchard on the outskirts of Liège. The surgical tent where Muriel worked 12-hour night shifts was where patients who came out of surgery went. Even with all the training, the sights and effects of war were hard: “We had no idea it would be as bad as it was. It seemed as though every patient that came in had some extremity amputated.”

Soon after their arrival, in November, Hitler started sending ‘buzz bombs’ into Liège to cut off all supplies and transportation to the Americans. These buzz bombs, each carried two thousand pounds of explosives and came over every twelve to fifteen minutes, twenty-four hours a day for the next two and a half months. As Muriel remembered, “Our hospital was hit three times, destroying tents and killing and wounding hospital patients and personnel. You’d hear them coming in the distance, putt-putt puttering along, and your heart would sink.”

On November 16th, the U.S. Army began an offensive against the German troops. Muriel recalled the one thousand beds in their hospital filling up almost immediately: “It was very difficult for us not to show any signs of emotion because they were so young, so handsome, and yet you knew that many of them would never have a normal life again.”